| By Sarah Max

Posted March 12, 2004 BEND, Ore. (CNN/Money) – Three years

after moving into a new 4,700-square-foot home in Brook Hills, a gated

community near San Diego, Sonni and James Bass are caught up in an expensive

legal battle with their homeowners association.

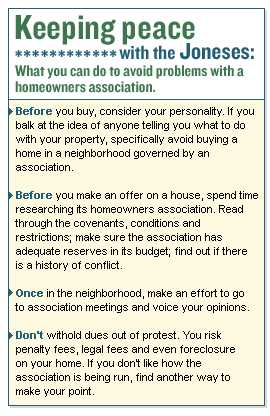

"Anyone who did extensive landscaping took more than a year," countered Sonni Bass. "I'm the only one who's being sued." As for the light on the tennis court, she said, "the board president threatened to remove it with a jackhammer." The squabble may sound familiar, because disputes just like it are happening across the United States. About one in six Americans lives in an association-managed community, according to the Community Association Institute (CAI). An estimated four out of five houses built since the late 1990s are governed by a homeowners association. As more people move to such places, the adage that fences make good neighbors no longer seems relevant. In fact, your neighbors might not let you even put up a fence.

Living by the rules

"The punishment does not fit the crime," said Michael Macomber, an attorney for Tom and Anita Radcliff, a retired couple in Copperopolis, Calf., whose home was foreclosed on by their association in January because the couple did not pay the $120 in annual dues they owed.

Not what you bargained for

"While the rules may seem arbitrary, you have to ask yourself, 'What if every resident did the same thing?'" said Rathbun. In other words, the fact that your neighbor can't put his car on blocks in the front yard is probably to your benefit. Critics of homeowners associations, however, argue that the bodies have too much power and not enough oversight. "There needs to be a regulatory agency that creates rules [of conduct for associations] and enforces them," said Jan Bergemann, a retired hotel owner and chef in St. Augustine, Fla. who founded Cyber Citizens for Justice. "Few people can afford to hire a lawyer just to get minutes from a homeowners association meeting." At the very least, say homeowner advocates, there should be more disclosure about the constraints of living in neighborhoods governed by associations. "You need to know that you're essentially giving up your property rights," said George Staropoli, a resident of a homeowners association in Scottsdale, Ariz., and founder of Citizens Against Private Government HOAs. Buyers typically don't get a copy of the association's CC&Rs until they close on their home or move in. Unless they specifically ask about association rules or a real estate agent points them out, they may not understand the implications of buying in a particular neighborhood until it's too late to back out. Even if homeowners do manage to get through the CC&Rs -- which are often written in legalese and inches thick -- they still may not understand the consequences of not abiding by the rules, said Staropoli. Sonni Bass certainly never imagined that her landscaping would turn into a high-stakes lawsuit. "I'll never move into another neighborhood with a homeowners association," she said. "I had no idea what we were getting into." |