Nathan Reiber retired

to Florida in the 1970s carrying more baggage than a

suitcase.

The Canadian lawyer would come to be hailed for his

philanthropy, rubbing elbows with celebrities and world

leaders, and donating time and money to charitable causes.

His South Florida building career was described as a happy

accident, a case of a shrewd retiree spotting a property and

launching the second act of his business career.

But by the time Reiber was building the Champlain Towers in Surfside in the 1980s, he was facing tax evasion charges in Ontario stemming from siphoning coin laundry money from his apartment buildings there. A warrant was issued.

|

|

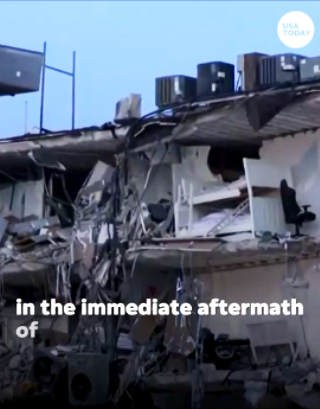

The report warned of

critical errors in waterproofing that had led to concrete

deterioration and damage to the columns and walls in the

lower levels. The cause of the collapse has not been

determined and may take more than a year.

While one Surfside official told residents the building was

in good shape after that report, owners and the condo

association board were concerned about the repairs, and the

sky-high price tag, which led to years of delays in getting

work started.

“We have discussed, debated, and argued for years now,” said

Jean Wodnicki, president of the association’s board of

directors in a letter to owners April 9.

Conditions had worsened since the 2018 report, she said:

“When you can visually see the concrete spalling (cracking),

that means that the rebar holding it together is rusting and

deteriorating beneath the surface.”

Reiber chose a bad year to build in Surfside. In 1980, the

cost of all construction materials, including such

structural necessities as rebar, neared a 30-year high,

according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. The bank

prime lending rate topped 15%, a staggering burden to anyone

hoping for a loan.

And Reiber already had been burned by the Florida market.

Along with Canadian developer Max Citron, his company had

bought two Miami-Dade apartment projects in the early 1970s

just as the market peaked. One faced foreclosure; the other

was reportedly sold at a loss. The investors even struggled

to pay landscaping bills: An unpaid Miami firm filed liens

in 1975 naming Reiber and Citron to get the $3,850 owed.

Shepherding Reiber through 1980s development was Miami

attorney Stanley Joel Levine.

Like Reiber, Levine was praised for his philanthropy when he

died in 1999; known for raising money for Fight for Sight, a

nonprofit researching blindness started by his mother.

Also like Reiber, Levine came to the Surfside development

following a brush with the law.

In 1969, Levine’s own lawyer walked him to the Dade County

jail where Levine turned himself in. Along with Miami City

Councilman Malvin Englander, a grand jury had indicted

Levine for conspiring to get $8,000 in bribe money from a

local woman seeking a building variance. Both men denied

wrongdoing. And the charges didn’t stick. A judge ruled that

Englander’s grand jury testimony had been coerced because he

believed he might lose his council job if he did not

testify. The case fell apart.

Reiber’s out-of-country tax charges might not have put off

potential financiers in the 1980s South Miami condo market.

In the cocaine cowboy years, the city had more serious

problems: Billions of dollars in drug money was flowing into

South Florida. And an unknown amount of that cash was being

laundered through real estate deals in a red-hot condo

market. The DEA sounded alarms. The IRS sounded alarms. The

cash kept flowing. With a drug-drenched reputation as sordid

as it was glitzy, the New York Times wrote in 1987 Miami’s

reputation was “a juvenile delinquent” among cities.

Grand juries in Dade County in 1989 and 1992 identified

numerous issues with the construction industry during

decades of rapid growth, including when the Champlain Towers

were erected.

“(Dade County’s Building and Zoning Department) does not

have enough building inspectors to competently conduct the

necessary number of inspections,” the 1989 grand jury wrote.

“Inspections are frequently conducted in a short,

perfunctory manner and some are not performed at all.”

Their report includes stories of roof inspectors who never

climbed ladders, building inspectors that checked off

properties they never visited, instead napping or going

bowling, and unlicensed contractors operating in the county

with little repercussion if caught.

The 1992 report focused on whether earlier shoddy design and

construction contributed to the devastation wrought by

Hurricane Andrew, and found in many cases it did.

Surfside, a tiny town of roughly 6,000 sandwiched between

BalHarbor and Miami Beach, had more mundane building

problems in 1979: Its outdated sewer system couldn’t handle

new development. Reiber and his partners wanted to build

twin luxury towers, Champlain Towers North and South, just

when the town could no longer build anything.

Campaign donations

Dade County had slapped a moratorium on construction in

Surfside because of the sewer concerns. The town needed

$400,000 for updates before it could green-light new

construction.

Reiber’s Champlain Towers Associates agreed to pay half the

bill. The moratorium was still in effect. Surfside officials

gave Reiber the go-ahead anyway. However, the town would not

issue a certificate of occupancy allowing anyone to move

into the condos until sewer upgrades were complete and the

county lifted the moratorium.

Buyers snapped up condos in the towers as soon as

construction began. An Aug. 10, 1980 ad in the Miami Herald

touting the towers’ “breathtaking views from every room”

claimed they had just 18 units left for sale between the two

136-unit buildings.

Also in 1980, Reiber and several associates bought a third

piece of land between the North and South towers, which

would become Champlain Towers East.

At the same time, accusations flew at town council meetings

that Reiber’s company was trying to buy friends on the

Surfside Commission. According to newspaper reports, the

developers gave $200 to one commission member and $100 to

another. Project Manager Joseph Miller, who made the

donations, told the Miami Herald the intention had been to

donate to all 10 people running for council that election,

but two had asked for money early.

When the contributions sparked controversy, Miller asked for

the money back. Councilman Saul Gromet, a perennial opponent

of the project, said he’d already spent it.

A second round of controversy started just as the county

lifted the construction moratorium in 1980. Zoning laws at

the time limited construction to 12 stories or 120 total

feet.

Reiber and his partners had revised their initial plans for

the towers to include penthouses, bringing the total height

to 123 feet: 12 stories plus one large penthouse on the top

floor of each building.

According to media reports from the time, the council voted

to approve the zoning variance because the wording on the

books was vague when it came to penthouses. They feared the

developers would sue if they weren’t allowed to add them.

The mayor vowed to change the zoning codes to be more clear

so they wouldn’t be put in that position again.

But one resident was so angry about that special variance

that he started a drive to recall the mayor, vice-mayor and

two commissioners who voted for it.

The exact date the South tower opened to residents is

unclear, but a newspaper report about a theft of personal

property at that address appeared in 1982 and ads reselling

furnished condos ran in 1983.

In 1981, work had also begun on the site of the future East

Tower, but at some point was abandoned. Eight years later,

the Miami Herald reported, that site sat as an eyesore with

construction debris left behind and stagnant water

attracting mosquitoes where excavation of a pool and

elevator shafts had begun.

Surfside gave the go-ahead to resume that project in late

1989 but not without more controversy including some

residents screaming down Reiber in public meetings,

according to media reports. They wanted assurances that the

property wouldn’t be left abandoned again. Construction

didn’t start until 1994, but the East Tower was eventually

completed.

A big splash

By the late 1980s, Reiber was enjoying success.

In 1988, when Elizabeth Taylor came to Miami to throw a

major AIDS fundraiser, donors paying up to $2,500 spread out

across the city for celebrity co-hosted parties at mansions,

clubs and on yachts. Zsa Zsa Gabor, singer Donna Summer,

Tommy Tune, and supermodel Lauren Hutton attended.

Reiber and his wife, Carolee, reportedly hosted one of the

parties on their 80-foot yacht RYE-BAR along with fashion

designer Fabrice, actress Susan Anton and actor Eric

Roberts.

He built a lavish home on Miami’s posh Star Island on a site

formerly owned by an in-law of Saudi royalty.

Reiber’s charity work was equally high profile.

According to his obituary, he met world leaders from Spain,

Hungary, Germany, Ethiopia and Uzbekistan while serving as

the National Executive Vice President for the Jewish

Institute for National Security of America.

But records show money troubles never went completely away.

Three subcontractors on the Star Island home filed liens

over unpaid bills. In 1994, Florida’s Department of Revenue

demanded Reiber's Nattel Construction Inc. pay $6,611 in

back taxes and interest.

In 1996, Reiber returned to Canada to settle up with tax

authorities over the tax evasion charges. According to an

Ontario newspaper, he paid a fine of $60,000.

Tax authorities also investigated the 1974 purchase of a

60-foot yacht, which landed in Florida. Reiber was asked why

no loan paperwork backed up the sale. “This is the way we

did all our business,” said Reiber, according to Canadian

tax court records. “All our other companies, the same thing.

It was not backed up by a note or anything else.”

In fact, it was other documents that the Canada Revenue

Agency inspector who looked at Reiber’s Florida yacht

records had been sent to Miami to examine. “This

investigation started with a lead ... not related to this

boat,” said the inspector in the tax court proceedings. “It

was to do with other false contracts.”

However, there are no online records showing tax authorities

found problems or filed tax actions against Reiber over

other contracts. The yacht loan dispute was decided in

Reiber’s favor, though the hearing officer criticized

Reiber’s conflicting statements, writing that, “The

appellant's credibility is elastic.”

Asked about its inquiry, Canada Revenue Agency declined to

comment, citing confidentiality restrictions.

Reiber and his wife sold their Star Island home in 1999. He

died in 2014 after a lengthy cancer battle, remembered as a

philanthropist and by his daughter as a sharp businessman.

“He enjoyed the game of business and was good at that,” Jill

Meland told the Miami Herald.

Members of Reiber’s family could not be reached for comment.