In the dimly lit

hallway of a South Florida condominium, a man in a white

fedora presides over an auction.

The prize is around the corner, a 700 square foot,

one-bedroom apartment left behind by a woman with dementia

who died estranged from her heirs.

|

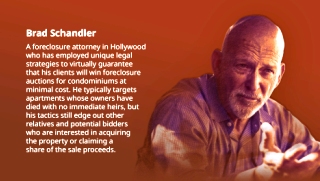

Attorney Brad Schandler, at right, prepares to preside over a foreclosure auction at Oakland Grove Village Condominium in Oakland Park, Florida on Tuesday, February 27, 2024. Auction bidders include Schandler’s sister, Nadine August, seen at center, and Mauricio J. Riquer, at left They are joined by court reporter Gary Siffort. |

His methods have been

described by attorneys as a “fraud and hoax” upon the court,

illicit “equity stripping,” and “brazen manipulation of the

court system,” but authorities have taken no action and

South Florida judges keep enabling him.

The cases point to a weakness in the Florida foreclosure

process at an especially dangerous time, as assessments and

liens are expected to increase to meet new condo maintenance

laws passed after the 2021 Surfside condo collapse.

The patterns the Herald found reveal how savvy lawyers can

work the system to wrest condos away from absentee owners

and the relatives of dead owners over liens as small as a

few thousand dollars. Heirs who lost out and legitimate

bidders who were shut out said they were shocked that

Schandler and his network have the courts’ blessing to

operate the way they do.

One woman said her family didn’t lose just their Kendall

condo, but also everything inside of it, and a Jeep parked

outside. Another said she fought to save her grandparents’

condo but lost the ocean-view unit and everything in it,

including the paintings. Both missed a legal window of

opportunity to collect their belongings.

Schandler, 68, who lives with his wife in a modest townhouse

in Hollywood’s Emerald Hills neighborhood, grew up in South

Florida. His parents, Bernie and Dolly, owned a Wolfie’s on

163rd Street in North Miami Beach in the ‘60s, ‘70s and

‘80s, according to his father’s obituary. He earned his law

degree at the University of Miami in 1983.

He said his tactics aren’t unique. “I know there are other

people probably doing similar things,” Schandler told a

Miami Herald reporter at the Oakland Park hallway auction on

Feb. 27.

In a written response supplied by his attorney on March 26,

Schandler said he uses an “alternative, legal foreclosure

sale method” to help condo associations quickly clear up

cases where an owner is in default and the condo may be

“long abandoned.” They are cases “where no property owner or

family member of a property owner remains with any interest

in the property.”

“Our clients can promptly pay the condo the unpaid fees or

assessments much faster than if the association paid a

lawyer to proceed with the foreclosure case, which can drag

on for months or years,” the statement said.

“In the rare instance where a distant family member emerges

late in the process, after the court has unsuccessfully

attempted to locate them, my clients and I make every effort

to resolve the foreclosure to the family member’s

satisfaction.”

How this secret system works

The Herald found nearly 30 cases in Broward and Miami-Dade

counties in which Schandler and associated lawyers used a

series of similar, unconventional tactics to game the system

and buy condos for a fraction of their market value.

Schandler and his network typically pursue properties owned

by the estates of people who have died and whose mortgages

were fully paid off, leaving no banks to complicate an

otherwise simple proceeding. In some cases, owners or heirs

live in other countries. The properties are often in

foreclosure over unpaid condo assessments or fees.

Schandler usually pays off the condo debt in exchange for

the right to try to recover that money through the

foreclosure case. That gives him standing to join a case and

request modifications to the foreclosure process.

The Herald found a pattern of Schandler persuading judges to

approve three unusual tactics that helped him upend the

normal foreclosure auction process and ensure a win:

-

On-site auctions: Instead of holding foreclosure auctions online, as is typical in Florida now, Schandler gets judges to let him hold auctions at the property. In the cases reviewed by the Herald, few if any competing bidders showed up to the in-person auctions.

-

No redos: While auctions typically are redone if the winning bidder fails to pay, Schandler has persuaded judges to declare that if the winner doesn’t make good on their bid, Schandler’s client can have the property, typically for $100.

-

Bidding credits: When the auction is held online, Shandler has persuaded judges to give his clients an unlimited “bidding credit.” They can bid as high as they need to win, but they don’t have to pay that amount. They are only required to pay the debt owed on the property and a little extra to cover fees.

Schandler’s Rules

When Brad Schandler becomes involved in condo foreclosure

cases, they quickly deviate from the norm.

Debt A condo owner incurs a debt, often from

non-payment of condo fees.

Case The holder of the debt, often the condo

association, files a foreclosure suit against the owner.

Judgment A judge approves a final judgment,

authorizing the sale of the property at auction and setting

how much money the holder of the debt is owed from the

proceeds.

Auction The property is put up for sale, typically

online. The proceeds from the sale are used to repay the

debt-holder.

Schandler's Rules Most auctions changed to on-site at

property. If the top bidder fails to pay, Schandler’s client

wins the auction for little cost.

Schandler's Rules In some online auctions, Schandler

gets a bidding credit which allows his client to bid an

unlimited amount but only have to pay the judgment amount

plus fees.

Proceeds Other parties can apply for any funds

leftover from the sale after the judgment has been repaid.

This is when other heirs could make a claim for surplus

funds.

Schandler's Rules After auctions with Schandler

rules, there is typically no surplus left over for heirs.

Ownership Once the sale is final, the winner of the

auction takes ownership, at which time they can either keep

the property or re-sell it.

|

|

“If a judge orders it, what can we say

other than that the judge was taken advantage of,” he said.

The courts effectively operate on an honor system, relying

on the good faith and accuracy of pleadings filed by

lawyers, said Broward Chief Judge Jack Tuter. “We’re not

investigators,” he said. “It’s very difficult for us.”

Schandler told the Herald he “didn’t

invent” the notion of holding foreclosure auctions in

person. They used to all be handled that way - on the

courthouse steps. Today’s online auctions, he said, can

attract bidders who don’t research ahead of time, default

after winning, and add delay and cost to the case. So, he

said, he borrowed tactics he’d seen in other cases, and

wrote auction terms he likes better.

“They are real auctions,” he said. “Anyone can appear.”

Schandler said in his written statement that the unlimited

bidding credits he wins on behalf of clients are

“innovative” but “not particularly unusual.”

But he declined to explain the rationale behind the credits.

“I am sure you understand that I am not going to discuss my

legal strategies with you,” he said.

Those strategies have been effective for Schandler. The

Herald found five instances in which his clients had been

granted this allowance, bidding just over $637,000 to win

the properties but paying only $134,000 to claim them.

Kitty and Katz

In the past 10 years, Schandler’s network has snapped up at

least 20 properties worth more than $4.5 million, according

to the Herald’s analysis of court records. Typically they

paid little more than the cost of the judgment associated

with the foreclosure, a fraction of the property’s value.

It isn’t clear how much of that money has made its way into

Schandler’s pockets. He declined to discuss how much he

makes from his work when asked by the Herald at the Oakland

Park auction, saying only, “It beats waiting tables.”

Schandler said in his written statement that the proceeds

from these transactions go to his clients, not him. He

declined to say who his clients are.

Though Schander told the Herald “I practice by myself,” a

small group of people have been present in many of his

cases, including attorneys Robert C. Meyer of Coral Gables

and Samuel R. Danziger (now deceased) of Miami, and a man

named Louis S. Katz, location unknown.

Schandler’s sister, Nadine August, appears to have been

involved in at least two of the cases examined by the

Herald. In one case she bid under her real name. In the

other, a competing bidder identified her as the woman who

bid under the name “Kitty Lefkowitz.”

Schandler’s network

A small group of lawyers and associates

has provided assistance in a number of Brad Schandler’s

foreclosure cases.

Schandler said he wasn’t comfortable talking with the Herald

about his cases or associates. In a written statement from

his lawyer, he said they were “colleagues” and have done

nothing improper.

Meyer and August didn’t respond to multiple requests for

comment.

The Herald was unable to find any public footprint in

Florida or contact information for Katz or Lefkowitz.

‘Something very dirty is going on here’

Right before the auction was to start on a two-bedroom

Pompano Beach condo with ocean views, a woman showed up and

said her name was Kitty Lefkowitz.

She joined a retired Realtor named Hernando Posse, who was

the only other bidder at the July 2021 auction at the

property, in foreclosure over unpaid condo assessments.

Schandler presided over the auction in the lobby of the

condo building, and it went quickly. As Posse recalled,

whatever he bid, Lefkowitz bid more. The price soon exceeded

what Posse could afford, and Lefkowitz won with a bid of

$185,000.

Lefkowitz never paid the full amount she owed, but the condo

didn’t go back to auction. Instead, thanks to a rule written

by Schandler and approved by Broward Circuit Judge Nicholas

Lopane, the property went for $100 to a company represented

by Schandler.

There would soon be doubts about whether Lefkowitz was

actually who she said she was.

When Herald reporters recently showed Posse a picture of

Schandler’s sister, Nadine August, he recognized her as the

bidder who gave her name as Kitty Lefkowitz.

August didn’t respond to questions from the Herald, and

Schandler didn’t respond directly to the Herald’s question

about whether his sister had posed as Lefkowitz. In his

statement, he responded: “the business of foreclosure

litigation and investing is ‘cut-throat.’ Many competing

investors may want to take whatever actions possible to

eliminate or defame and disparage their competition or the

attorneys representing competing interests.”

Posse said he’s still upset about losing out on the

apartment. He said he had been bidding in auctions for

months hoping to find an affordable place to live in a

region where such properties are in short supply.

“I needed a roof, I needed a place to live. That apartment

would have been perfect,” he said. “Something very dirty is

going on here and Brad Schandler is the engineer of it.”

Posse recently complained to the Florida Bar about what he

saw. A Bar spokeswoman said they’d received an “inquiry”

about Schandler but there was not “enough information to

rise to the level of a legally sufficient complaint.”

Posse wasn’t the only person shut out of the auction.

The apartment had belonged to Kori Delcourt’s grandparents,

whose closest relative was her uncle. It was only after her

uncle died in summer 2021 that she learned it had been

foreclosed.

Delcourt’s lawyer, Jordan Wagner, couldn’t find any record

of Kitty Lefkowitz, and the only address listed for her in

the court records was the property address itself.

Wagner submitted a scathing 70-page court filing in November

2021, seeking to undo the sale and highlighting what he

called a “pattern of fraud, misconduct, and brazen

manipulation of the court system.”

As Delcourt recalls, Schandler was eager to settle. She

reluctantly agreed to the settlement — whose terms she can’t

legally discuss — and withdrew her motion to overturn the

sale, convinced it would be hard for her to win a better

outcome. Years later, she is still upset that she lost the

apartment.

The condo was sold in late 2022 for $520,000 by a company

affiliated with one of Schandler’s associates. It’s back on

the market now, with an asking price of $650,000.

‘How did you know about this?’

Tamir Ness was serving on a condo board at the Nine at Mary

Brickell Village in Miami when he learned one of the units

was headed to an auction to be held in the building. Ness

decided he’d go.

The auction was held in front of the elevator on the 27th

floor. Ness said anyone who didn’t live in the tower might

have been turned away by security guards, who were unaware

the auction was taking place.

When he spoke with Schandler to arrange giving him a

cashier’s check ahead of time, a prerequisite to participate

in the auction, Schandler asked him, “How did you know about

this?”

Robert Meyer, the auctioneer that day, didn’t kick it off on

time. He said he was waiting for another bidder to arrive

and that if Ness didn’t like it, he could leave.

Meyer left, then returned 15 minutes later with the bidder,

who gave the name Louis Katz.

Ness said he later viewed security footage and saw that

Meyer and the bidder had arrived in the lobby together that

morning.

The auction started 39 minutes late. Within three minutes,

the bids were up to $430,000, and the man who identified

himself as Katz won.

“I just kept bidding, bidding and I just stopped,” Ness

said. “I could have gone to $10 million and he’d keep

bidding.”

The next day, Katz didn’t pay the $430,000. So, by the terms

of the auction approved by Miami Circuit Court Judge Renatha

Francis (now on the Florida Supreme Court), the ownership of

the condo went to Schandler’s client, a trust connected to

Danziger.

Ness was in for a further surprise when he received a

transcript of the auction and learned that the man who said

he was Katz and put in the winning bid at the auction was

identified in the transcript as Brad Schandler.

Thanks to the wording in Judge Francis’ order — written by

Schandler and adopted verbatim by the judge — Schandler paid

just $3,478 in condo debt to win the property.

Judge Francis declined to comment to the Herald, citing

judicial codes of conduct that prevent her from discussing

specific cases.

Ness’s lawyer filed a motion to reverse the sale on the

basis of “fraud, misrepresentation, irregularity in the

conduct of the sale and collusive bidding.”

“This gentleman is very creative, and he knows how to work

around the law and ... he just knows these loopholes and he

knows how to play the courts,” Ness told the Herald. “His

wisdom and his experience unfortunately outweighs everyone

else’s ignorance.”

Before things went any further with Ness’ complaint, the son

and daughter of the condo’s deceased owner — a Kuwait

resident — found out what happened and objected to the sale

of the condo, saying they were the legitimate heirs.

The foreclosure case ultimately settled out of court, with

undisclosed terms.

‘Keeping rightful heirs from what they were entitled to’

When foreclosure sales occur, relatives and other connected

parties can petition the court for a portion of any sale

proceeds left over after the debt from the property has been

repaid.

Schandler ensured that Lori Evans didn’t get a penny when

her cousin Erik Lemberg died, leaving behind no children and

a two-bedroom condo in Tamarac.

“Erik and I were very close growing up,” she said. “I

literally talked to him three days before he died.”

Evans didn’t have the money to take on her cousin’s

property, which had fallen into disrepair and was headed to

foreclosure over unpaid condo assessments. A lawyer told her

she might still be able to claim a portion of the proceeds

when the apartment was sold at auction.

“It would have definitely helped me in a big way,” said

Evans, who raised her daughter alone in the Atlanta suburbs.

Given the value of the property and the $15,000 debt owed to

the condo association, Evans’ lawyer estimated her portion

of the leftover funds could be more than $30,000.

But Schandler convinced Broward Circuit Judge Florence

Taylor Barner to give his client a mind boggling advantage —

an unlimited bidding credit. Schandler’s client could bid

any amount in the online auction, but would only have to pay

$20,000.

Deep discounts In several foreclosure cases, Brad Schandler

has convinced judges to allow his clients to bid anything

they want at online auctions, but only be on the hook for a

little more than what is owed on the property.

Schandler’s client won the auction for $95,800, beating out

numerous other bidders, including one who bid $95,700. Court

records show that the bidder name associated with that

winning bid was Adonai Lee, which translates to the “Lord is

with me” in Hebrew. While the same bidder name, Adonai Lee,

was associated with the winning bid in at least two other

auctions won by Schandler’s clients, Schandler said in a

statement that the name was listed incorrectly and that he

“was not responsible for these forms, prepared by the

clerk.”

Had Schandler’s client been forced to pay the full amount

for the Tamarac condo, there would have been a surplus of

roughly $80,000 and Evans likely would have been able to

claim a portion of it.

“It just seemed like it was a scheming way of doing business

and keeping rightful heirs from what they were entitled to,”

Evans said.

Schandler’s client, a trust that lists the same address as

Schandler’s virtual office, still owns the property, which

is valued at a little more than $160,000.

‘We lost everything’

Schandler has used these online auction rules at least once

to win control of a property from owners who were still

alive, but living abroad.

Living in Peru and not understanding English well, Jose

Manuel Aramayo didn’t have a good grasp of what was

happening with his Kendall condo when it was foreclosed in

2018, his daughter, Maria Aramayo, told the Herald.

While he owned the condo free and clear, he had taken out a

mortgage on it in 2017, and soon defaulted when an

investment went sour. He owed the $15,000 on that mortgage,

plus another $7,000 in fees and $7,099 in unpaid

assessments.

He was consumed by depression, his daughter recalled, and

didn’t tell family members what was going on.

Schandler convinced Miami-Dade Circuit Judge John Thornton

Jr. to give his client an unlimited bidding credit when

Aramayo’s foreclosed condo went to auction. So while his

client won the auction with a bid of $150,400, it only paid

$23,646.08, court records show.

Miami attorney John Paul Arcia tried to get the condo back

for the Aramayo family, arguing that Thornton had erred in

hastily signing a “nefarious court order” less than two

hours after it was submitted by Schandler. He said it had

been “intentionally drafted in a confusing manner so as to

not arouse suspicion of its devious purpose.’’

He alleged that Asset Recoveries LLC, a Schandler- and

Meyer-affiliated entity that ultimately paid the winning

bid, engaged in “equity stripping.” “The facts of this case

are appalling, unjust, unconscionable, inequitable and it is

hard to believe that these facts have actually transpired,”

Arcia wrote.

Thornton retired from the bench soon after. Now a mediator

and arbitrator, he did not respond to multiple requests for

comment. Asked to reconsider what Thornton had done,

Miami-Dade Circuit Judge Oscar Rodriguez-Fonts ruled that

Schandler’s client had been entitled only to a $7,099

bidding credit, but it was too late in the judicial process

to undo the mistake. An appeals court upheld

Rodriguez-Fonts’ decision.

Without the unlimited credit, Arcia argued, Aramayo would

have been entitled to more than $100,000 left over after the

small judgment was paid.

He got nothing. Even the contents of the condo were taken,

Maria Aramayo said. Schandler, through his attorney, said

Aramayo had more than three months after losing ownership to

remove his belongings.

“We lost everything,” Maria Aramayo said. “Everything that

you could have in an apartment to live, like everything.”

Gone were photo albums, a grandmother’s sewing machine, the

Jeep Patriot that she and her husband drove when they were

dating.

Jose Manuel Aramayo had bought the condo when his son was

studying in Miami, and he thought his daughter could stay

there when she visited from Indiana. It was an investment,

and a safe one, or so it seemed. Losing it wrecked her

father for a time, she said.

“He was just consumed then by this depression, anxiety and

the fear of losing the apartment because that would have

been something he would have used for his retirement,” she

said in an interview. “I couldn’t believe the judge or the

court would allow this.”

Asset Recoveries still owns the two-bedroom, two-bathroom

condo, now valued at $215,814.

‘A scheme perpetrated by misrepresentation’

Arcia isn’t the only lawyer who has raised alarm bells about

Schandler’s activity, but those warnings have never resulted

in consequences.

In November 2017, Schandler tried to intervene in a Fort

Lauderdale condo foreclosure, saying he represented a trust

affiliated with Samuel Danziger that paid the cremation

costs of the condo’s owner, Susan Koskey. He said the trust

was assigned the right to collect that debt.

Broward County Circuit Judge Martin Bidwill allowed

Schandler to intervene in the case, but reversed his

decision when Ashley Tulloch, a lawyer representing the

condo association, established that Schandler had not paid

the medical examiner’s office that cremated Koskey and that

the office didn’t assign anyone the right to collect payment

for debts.

Bidwill blocked Schandler from joining the case, ruling that

he carried out “a scheme perpetrated by misrepresentation.”

But he took no action to hold Schandler accountable.

Tulloch filed a report with Fort Lauderdale police. But the

police report showed that the case died after officers

talked to another lawyer involved who told them that there

were no victims because Koskey died with no heirs.

But Koskey did have relatives. And fortunately for them,

Schandler wasn’t allowed to rewrite the rules of their

auction. The sale yielded a surplus of nearly $150,000, and

a handful of relatives collected a portion.

Koskey’s 80-year-old cousin, Barb Brenna of Cook, Minnesota,

said she thought of the $12,000 payment she received as a

“gift,” but would have been upset if the family had been

denied a share of the proceeds because Schandler had changed

the rules.

“It makes my heart sick when I think that somebody took

something that belonged to somebody else,” she said.