PALM BEACH GARDENS — The residents of the Bent Tree community in Palm Beach Gardens were loud and clear when the new Southampton townhouse community, just to their south, came to city council members for approval: We want it to be two stories, not three, they said, with some pointing to developer greed as the only justification for the extra story.

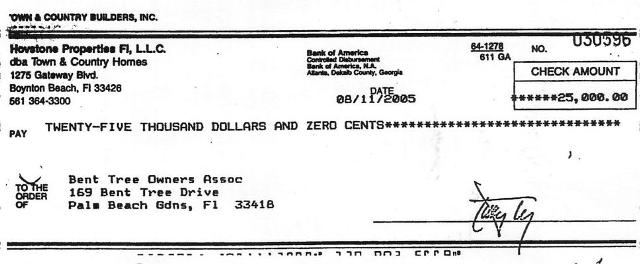

THE NEIGHBORHOOD: The Bent Tree subdivision's association accepted $25,000 from Hovstone Properties Florida to 'reduce the possible noise.' The check was divided among the 11 homeowners, each of whom received $2,272.72. But finally, an agreement was struck. Some, but not most, of the buildings were reduced to two stories, and some changes were made to the architecture. Another part of the deal was cash. The Bent Tree Property Owners Association was pledged $25,000 by developer Hovstone Properties Florida, money that was later divided among 11 homeowners who were free to spend it however they liked. Residents dropped their opposition. And the gift, made last year, wasn't publicly discussed. Bent Tree couple Joel and Barbara Buschek, aghast at the payment that was hashed out between the developer and a few residents, recently moved out of the area, calling the city corrupt.

THE DEVELOPMENT: Hovstone Properties got the go-ahead on these Southampton townhomes next to Bent Tree after Bent Tree dropped its complaints and received $25,000 from Hovstone. The recipients could spend the money any way they chose. They were particularly disturbed by the silent acquiescence of their elected officials. "The whole thing stunk," Joel Buschek said. "What they did was teach the homeowner's association you can operate in secret and get away with it." Developers have routinely enhanced their projects in various ways to appease residents or elective bodies. Sometimes they add trees or bushes. Sometimes they include another patch of lawn. Sometimes, they make design changes. And sometimes, they make a payment in cash. Bent Tree is just one example. In West Palm Beach, a $250,000 gift from The Related Group was pledged clandestinely to a neighborhood association the day before a commission vote on a condo project last year. Residents heaped praise on the project, and city commissioners granted the project exceptions to city rules. Not all of the payments are made secretly. A promise of $5 million for minority economic and educational programs sealed Palm Beach County Commissioner Addie Greene's vote for the winning Scripps site earlier this year. An official complaint led the state ethics commission to rule that the gift wasn't illegal but that involvement by Greene in disbursing the money might be improper. A foundation overseeing the money that's been formed since then does not include Greene as a member.

In another Palm Beach Gardens case, the city council in May accepted $500,000 for a trolley or light bus system from developer Kolter Communities when it approved a waiver allowing two, 12-story condo towers called Gardens Pointe in an area with a height limit of about four stories. They reasoned that waivers may be granted if the city benefits. Later, council members had second thoughts, saying the deal was a venture into "fairly treacherous waters" and that money for transit shouldn't come "at the sacrifice of our quality of life." But the condo approvals stood. In St. Lucie County, cash was exchanged after a vote. United Homes donated $250,000 to county commissioners in April several weeks after a development was approved. Commissioners, who received $50,000 each and said they plan to give it to nonprofit groups, said the gift came as a surprise. Part of the reason for the payments to neighborhood groups, developers say, is elected officials' demands that they pave the way for a smooth approval by negotiating with residents. They defend the gifts as attempts to be good neighbors and to improve areas where they do business. The payments also make life easier for the elected officials, who don't have to deal with neighborhood complaints that are addressed in side agreements. Some officials criticize this as effectively delegating government to neighborhood leaders. In the case of the Southampton townhomes, Leonard Ingrando, the president of the Bent Tree Property Owners Association who signed the $25,000 agreement, refused to discuss it. "He's not interested in speaking with you so it's not necessary to call back," said a woman who answered his phone in Tennessee, where Ingrando has since moved. Eleanor Halperin, Hovstone's attorney, declined to comment. Steve Liller, the Hovstone official who oversaw the Southampton project, didn't return two phone calls. When the Southampton townhouse project was first up for approval on April 21, 2005, Bent Tree residents complained that they wanted it to be only two stories high. City code allowed either two stories or 36-foot-tall buildings. The buildings proposed were less than 36 feet tall. The developer also noted that it had the right to build more units than proposed and was preserving more open space than required. But residents weren't happy. "There is no legally justifiable reason for granting a waiver for three stories," Bent Tree resident Ruth Peeples told council members. "The only reason to grant a waiver is purely for economic reasons for the developer." Another resident, Fran Heaslip, said she'd factored in the existing zoning when she moved to Bent Tree. "If it had been zoned or even indicated that it might be three stories there, we certainly wouldn't have bought our house in there," she said. Council members delayed their vote, telling Hovstone to again try to resolve residents' complaints. On May 19 of last year, the project came up again for a vote. Developer representatives said they'd lowered the more visible buildings, those along the road and next to Bent Tree, to two stories. And improvements to the architecture were made. No residents complained. But word about a pledge of cash from Hovstone to Bent Tree had leaked out, and it made Councilwoman Jody Barnett, now vice mayor, uncomfortable. "I would appreciate it if you could tell me what the terms of that agreement were," she said. Hovstone attorney Halperin told her there was an "oral agreement" but declined to discuss it, saying, "I think that's between Bent Tree and the developer." But Barnett insisted she wanted to know exactly how the developer had ironed out differences with Bent Tree. Mayor Joe Russo told her the agreement had nothing to do with the buildings' height, but with concerns about noise, which had not been a major cause for objection during the public hearing in April. "I'm not interested in that agreement," Russo said. And Barnett finally dropped it. Her comments about the agreement don't appear in the printed minutes of the meeting. As it turned out, the $25,000 payment to Bent Tree from Hovstone, finalized three months later, didn't have to be spent on anything having to do with noise-reduction. In fact, the developer had already agreed to keep a 100-foot-wide natural preserve area between Southampton and Bent Tree, which promised to help with noise far more than a little extra landscaping would. Eleven homeowners who lived closest to Southampton each received a check for $2,272.72, along with a letter that said, "Although this payment may be used for any purpose you choose, it is our suggestion that the money be utilized for measures which will help reduce the possible noise." Russo said recently that he didn't want to discuss the money at the public meeting because the city attorney had said the council could only consider whether the project fit within the city's zoning codes — not arrangements between developers and neighborhoods. "We've always been advised by our attorney not to get involved in that — it's a separate thing," he said. At the same time, he doubted that the payments affected residents' opinions. "I don't think anybody, for $2,000, would sell their quality of life," he said. He said he didn't know that the money was free to be spent however the homeowners chose. "If I would have known that individuals were getting dollars instead of mitigation I would have felt differently about it," he said. "There's no question that a cash payment for anything is wrong." But about a year ago, Bent Tree residents who were outraged by the payment demanded an investigation and sent paperwork to the city documenting it all, and nothing was done. "I'm very disappointed in the management of the city of Palm Beach Gardens, and when they tell me something now, I have to believe it's a lie," said Bent Tree resident Ann Gott, who explained she wasn't opposed to the development but to the secrecy of the city and the Bent Tree Property Owners Association. Two homeowners who received a payment said they spent most or all of their money on landscaping. Another said she "would prefer not to answer." The others either didn't return calls or couldn't be reached. Council member Barnett said cash payments, especially to neighborhood groups, are inappropriate because it might encourage residents to try to cut deals with developers rather than engage in public discourse. "It has a chilling effect on that community voicing their opinions on what's going to happen next door," she said. "If deals are cut in private, is that ever really the best solution? And if it is the best thing for the community, why wasn't I allowed to ask the question?" She said elected officials need to represent residents more effectively so that residents aren't tempted to broker backroom deals. "They trust in their own power of negotiation better than trusting what the city commission will do for them," Barnett said. Gott said the controversy in Bent Tree has destroyed the neighborhood. "It used to be a wonderful community," she said. "Now it's total night and day in that community after this whole trauma that went on. So many people have moved out. So many people have no regard for the community. They just want to be left alone." Even worse, such cash payments pave the way for others, Joel Buschek said. "What's to stop the corruption from blossoming?" he said. "I mean, if you can do it for this amount of money, why not do it for more? If a developer can give this money, that's dangerous — a very dangerous situation, I think, with regard to our government." Developer's secret $250,000 gift to woo neighborhood group splinters residents |

| HOA ARTICLES | HOME | NEWS PAGE |