|

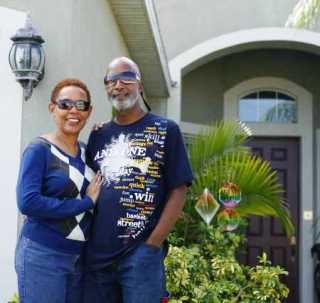

Article Courtesy of The Tampa Bay Times By Mark Puente Published February 23, 2012 RUSKIN — The housing bust shattered the American dream for millions of Floridians, but Albert and Bonita Davis should not have been among them. They make their mortgage payments. Both have jobs. Their "American nightmare,'' as Albert puts it, is the subdivision, River Bend, where they live. It has become a place where weeds have overtaken sidewalks and broken light poles dot the streets. A pool sits empty; the clubhouse remains half built.

gradually shed the expense as home buyers assume a proportional share. But when buyers don't come, the development goes broke. In that case, the law ensures that CDD bondholders get repaid first. Since land values have plunged so drastically, little or no money is left to pay off the bank mortgages on the same property. River Bend, for instance, had an original bond debt of nearly $20 million. Of that, $9.9 million is outstanding. Bondholders have started foreclosure proceedings. Banks can foreclose, but that would obligate them to start making CDD payments, which few want to do. About 48 Tampa Bay CDDs are in or near default, according to Richard Lehmann, a Miami Lakes businessman who tracks the state's nearly 580 CDDs in a publication called Debt Securities Newsletter. The letter is controversial because even when bondholders agree to restructure debt or bring the debt current, Lehmann doesn't drop neighborhoods from the default list. Of Tampa Bay's 115 CDDs, according to Lehmann, 25 are in some stage of default and another 23 could be teetering toward going broke. Most of them are in Hillsborough and Pasco counties. The original debt adds up to more than $100 million in the Tampa Bay area alone. William Rizzetta, president of Tampa-based Rizzetta & Co., which works with bondholders to manage some of the districts, stressed that the situation is not as dire as Lehmann's numbers would suggest. "When done right, (CDDs are) a good mechanism to use," he said. "The underwriting nowadays is more substantial." In a pattern familiar to Tampa Bay residents behind on their house payments, banks are pushing homeowners in CDDs into short sales. Banks lose less money in short sales than by seizing houses in foreclosure. Regardless of whether bond debt is restructured or land is seized, money losses will follow. Tampa-based Lerner Real Estate Advisors works with developers, builders, lenders and investors on distressed properties throughout the Southeast. In the past 26 months, the firm has provided services to more than 40 developments with 43,000 residential lots. President Harry Lerner said the goal is to get many failed developments "back up and running." Many national builders, he said, are buying some of the distressed lots. A key factor, Lerner said, is that once the nondistressed subdivisions start to dwindle more, builders will shift to the distressed properties, adding: "Builders are interested in these deals." Of the 762 lots in River Bend, 258 remain vacant. Residents are fighting to keep River Bend viable. Some help maintain the common areas. Albert Davis said he has stopped paying his yearly CDD fees of $1,688 because his subdivision sits in shambles. Still, Davis knows that thousands of other homeowners are fighting the same battle. "It's a feeling of hopelessness," he said. "This is our dream home. We are doing everything we can to hang on to it. Sometimes, that doesn't make sense." |