|

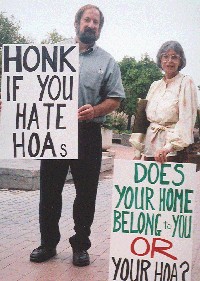

Article Courtesy of Tucson Weekly By TIM VANDERPOOL Published October 28, 2004 OK, maybe they aren't raising holy hell. But milling about the Pima County Courthouse, a band of buttoned-down, middle-aged, disgruntled homeowners sure are unleashing a little heck.

"It's chilling," Sadai says. "It's everything that I have, and now this gang in the homeowners association is trying to take it away." Barr agrees. Associations are only able to get away with their shenanigans, she says, "because people don't say anything; they don't get proactive. And even when they do, it's like David going up against Goliath." Backing Barr, Sadai and Dougherty is the Coalition of Homeowners for Rights and Education, or CHORE. Born in Arizona, and now reaching across the country, CHORE has become a far-flung warm-bed of reluctant activists teaming to fight the Man--in this case, homeowners associations drunk with power. CHORE has its work cut out. Promising to maintain property values and keep neighborhoods spiffy, HOAs are mushrooming across the United States. But they're also pushing many Americans across the fence-line of civility. Heavy-handed rules and arbitrary enforcement are often blamed for pitting neighbor against neighbor, and turning serene subdivisions into raucous battle zones. This is not a new phenomenon. With roots in 19th century Boston, these quasi-democratic bodies--also called residential community associations or common interest developments--now number more than 200,000. An estimated 42 million people currently live under their rules, and today, it's nearly impossible to purchase a home that doesn't come with an association attached. Typically installed by developers to govern budding villages, they provide amenities ranging from recreation centers to trash pickup. Under their tutelage, parks are established, swimming pools maintained and architectural consistency imposed, all financed by membership fees. Rules are set through deed restrictions and overseen by boards of directors comprised of neighbors and developers' representatives. Along with promoting a comforting uniformity, they also control the minutiae of daily existence for affected residents, right down to where you plop your petunia patch. All too often, say critics, that power is abused by neighbors with scores to settle. Those mandates often include big fines for tiny infractions such as planting the wrong type of shrubs, leaving a garage door open or even erecting a flagpole. Failure to pay up can mean a lien against your home, or even foreclosure. The result may be a national backlash, says Evan McKenzie, a University of Chicago researcher, and author of Privatopia: Homeowner Associations and the Rise of Residential Private Government. The book is highly critical of many association practices. Left unchecked, they "can really create little neighborhood Hitlers," McKenzie said in an earlier interview with the Tucson Weekly. Still, he's guardedly optimistic that the HOA juggernaut sees a need for change. "I think they realize that it comes down to giving these communities a chance to become communities," he says. Lawmakers are listening as well. Arizona legislators recently passed statutes preventing HOAs from seizing homes for unpaid fines, and requiring that they follow open meetings laws. Other rapidly growing Sunbelt states with a plethora of associations, such as Nevada, are following suit with crackdowns on association excesses And Texas lawmakers have tightened due-process procedures for legal actions against homeowners. Among those now also trumpeting reform is the Community Associations Institute, a Washington, D.C.-based trade group for association managers, lawyers and homeowners. Such efforts represent a shift for CAI: When McKenzie's book was published in 1994, an institute spokesperson labeled it "tabloid journalism." But on the ground, the CAI is still fighting reform every step of the way, says CHORE President Pat Haruff. To get new HOA laws through the Arizona Legislature, Haruff's group broke sweeping changes into bite-sized chunks. "Then the CAI lobbyist complained that there were too many bills," she says. "Earlier, he claimed that the combined bills were too big." By phone from Mesa, Haruff contends that associations have become battlegrounds because lawyers make windfalls. For example, if a homeowner "gets fined $100 for not cleaning his yard and refuses to pay, then the homeowners association takes him to court to collect. And by the time the court rules against the homeowner for a $100 fine, the attorney has made $8,000 to $10,000 in fees." In turn, this pattern is driven by the CAI's claims "that HOA's will go bankrupt if they refuse to go after deadbeats for fines," Haruff says "But you know what? There has never been an association that has gone bankrupt for that reason." There's certainly no shortage of associations--or lawyers--where Rick Happ lives in New Bern, N.C. A polite electrical engineer in a beard and sensible shoes, Happ became radicalized after buying a couple of country acres with a fenced road. Soon, his HOA was demanding the gate removed. He refused, and $100,000 in legal fees later, he won in court. Now Happ has flown all the way to Tucson to support Mika Sadai. "Look at how much money this has cost her," he says, outside the courthouse. "I was lucky I was able to fight back. The average homeowner wouldn't have been able to do that." As 2 p.m. nears, Sadai is getting nervous and lights up a smoke. As it turns out, the judge won't make his decision today. But that only delays the outcome she's sweating at the moment. Nearby, a well-dressed woman holds a sign high, and pigeon-holes passers-by. "If you care about your rights," she hollers, "don't buy a home in a homeowner's association." Pausing, the woman says she's from Indiana, and won't give her name because she's under a gag order. She fought her association over organic shrubbery. "And now I'm losing my home when I go back. But I'm a Christian, and I don't think God gives you more than you can deal with." |