When Eileen

Breitkreutz filed a request to inspect her condo

association’s financial records six years ago, she had no

idea it would spark six years of litigation and a $395,554

judgment against her.

Now, the registered nurse and single mother is talking to

bankruptcy lawyers to find out whether she’ll be able to

keep her home.

“I don’t know how they can do this. I don’t know why nobody stops them,” Breitkreutz said about the Boca View Condominium Association’s legal fights against her and several other unit owners who have asked to see their community’s books.

|

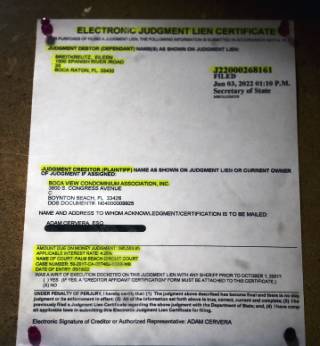

Eileen Breitkreutz, a condo unit owner at Boca View Condominiums, is stuck with a $395,554 legal bill after losing a years-long court battle that began with a request in 2016 to inspect her condo board's financial records. |

Breitkreutz feels it was posted there by association president Diana Kuka as “a warning” to others not to challenge Kuka’s authority.

The South Florida Sun Sentinel emailed three of the association’s Becker attorneys a list of questions raised by residents. The emails also sought an interview with Kuka to ask about the residents’ claims, and to ask why relations at the complex are so contentious. As of this story’s publication date, her attorneys have not answered the questions nor has Kuka agreed to an interview.

|

The lien on condo owner Eileen Breitkreutz's home is posted in the mail room at Boca View Condominiums. Breitkreutz is stuck with a $395,554 legal bill after losing a years-long court battle that began with a request to inspect the condo board's financial records. |

The Shefets:

In 2013 and 2014, David and Dganit Shefets, of Harrisburg,

Pennsylvania, transferred ownership of two units to a

company they formed, Cool Spaze LLC, for the purpose of

leasing the units. But the association board refused to

process and approve lease applications, stating the Shefets

did not seek board approval to transfer ownership of the

units. The Shefets sued, contending that the association’s

governing documents did not require approval of sales. That

lawsuit is ongoing, with 348 documents filed through June 3.

In August 2016, Cool Spaze filed a request to inspect the

association’s financial records. The association denied the

request, saying Cool Spaze was not entitled to see the

records because it was not an association member.

The Lepselters: Edward Lepselter, a unit owner and

Realtor with Remax LLC, filed two lawsuits in 2013. The

first suit named Kuka as defendant. Lepselter claimed Kuka

spit on him and called him “white trash” during a board

meeting and denigrated his and his wife Eleanor’s work as

Realtors in communications with other residents and Remax.

Both parties agreed to dismiss the matter after the couple

filed a separate lawsuit against the association.

The second suit, filed less than a month later in small

claims court, sought $1,364 for damage to the couple’s unit

that Leselter said was caused by a broken water pipe that

the association failed to maintain.

In December 2013, a county judge ruled in the association’s

favor in the pipe case, finding the Lepselters were not

entitled to damages because the association had offered to

have its own contractor make the repairs. But in April 2014,

the same judge shot down the association’s claim that its

attorneys were entitled to recover $120,000 in legal fees.

In her ruling, County Judge Sandra Bosso-Pardo wrote that

the $120,000 bill was unsupported by the attorneys’

documentation. “The amount claimed in this case shocks the

court,” the judge’s ruling stated. “In reviewing defense

counsel’s time records it is clear that many entries are

duplicative, unreasonable, unnecessary and excessive.”

After the association unsuccessfully appealed the denial of

their full fee request, Lepselter was ordered to pay about a

third of the original amount — $32,290.

Of 287 filings in the case, fewer than 100 involved the

original complaint and the rest dealt with entitlement to

attorneys’ fees and how much money the association would be

allowed to recover.

On Wednesday, Oct. 12, 2016, Breitkreutz submitted her

request “for myself or my authorized representative” to

inspect and copy association records. She sent the request

to the association’s property manager, Pointe Management

Group Inc., via certified mail as required by state law, and

cited the law’s requirement that the records be made

available within five business days. (A change in state law

now gives associations 10 business days to provide records.)

Records she sought spanned 2014 to 2016 and included annual

operating budgets and reserve budgets, monthly financial

statements, annual audits or reviews, bank statements,

detailed ledgers, receivables for each unit owner, paid

invoices, and invoices for legal representation.

On Friday, Oct. 14, the date the certified letter was

scheduled for delivery, Breitkreutz sent an email to the

property manager that she noted was a follow-up to her

formal request. The email requested an appointment to

inspect the records on any business day during the upcoming

week.

The record request was a verbatim copy of one the Shefets

had sent two months earlier and were told would not be

fulfilled because of the Cool Spaze deed transfer dispute.

In a later deposition, Yellin’s partner Ryan Poliakoff (son

of Becker co-founder Gary Poliakoff), acknowledged that

their firm, which also represents the Shefets, looked for

“other concerned owners” to submit the record request. The

Shefets, Breitkreutz later testified, agreed to pay for her

legal representation if the association fought the request.

A short window

Breitkreutz said she fired up her computer on late Thursday

afternoon of the week after she mailed her request and found

an email dated the previous day, Oct. 19, at 5:15 p.m. It

was from the property manager informing her that “the

association is setting your date and time” — less than 24

hours later — “for inspection of records.”

As she looked at the email, Breitkreutz realized the

scheduled day was now and the time — 3 p.m. — had passed.

Quickly she emailed Ryan Poliakoff, one of her two

attorneys: “I just opened this letter and realized the time

has passed. Please advise.”

Thirty minutes later, Poliakoff emailed Becker litigator

Robert Rubinstein, who was handling the request for the

association, and asked to reschedule.

Two minutes later, Rubinstein responded: “I will find out

what other days you can inspect the records and thanks for

letting me know you will do the inspection.”

Ten days later, after two more emails from Poliakoff,

Rubinstein responded, “Ryan, I do not know what to tell you,

other than I have never heard back from the Association and

I do not expect to hear back from them.”

It was clear to Breitkreutz and Poliakoff that the

association had no intention of making the records available

again.

‘It can get very

expensive’

On Dec. 5, 2016, Breitkreutz filed a petition seeking

arbitration by the Department of Business and Professional

Regulation’s Division of Land Sales, Condominiums, and

Mobile Homes.

Arbitration requests are a required first step in disputes

between unit owners and association boards, and arbitrators’

decision, while nonbinding, are typically accepted by unit

owners and associations, says Jan Bergemann, president of

Cyber Citizens for Justice, which bills itself as the

state’s largest statewide property owners advocacy group.

“People don’t want to spend the money [to appeal] because it

can get very expensive,” he said.

In Breitkreutz’s case, the arbitrator found that the

association “willfully denied” her record request by giving

her less than 24 hours’ notice, “thereby failing to give

[her] a reasonable opportunity to inspect its records,”

according to the order issued on April 8, 2017. The

association was ordered to provide Breitkreutz access to the

association’s records within 10 days and pay “the maximum

statutory damages of $500.”

Breitkreutz got neither access to the records nor the $500.

On July 5, 2017, the association sued her in Palm Beach

County Circuit Court. Becker attorney JoAnn Nesta Burnett

filed a complaint asserting that the arbitrator’s decision

“misapprehended the law and the facts.”

In its complaint and in later filings over the following

five years, the association not only argued that it

fulfilled its requirements under state law by granting

Breitkreutz access to the records, it also called into

question her motives for making the record request.

The association argued that it was unknown whether

Breitkreutz was telling the truth when she said she didn’t

open the email scheduling the record inspection until after

it was to have taken place.

The association argued that Breitkreutz purposely missed the

records inspection so she could file her petition for

arbitration and “leverage claims” by her attorneys’ other

clients, the Shefets, in their lawsuit over the deed

transfers.

In another filing, the association claimed the Shefets

enlisted Breitkreutz as a “straw person” to make a record

request identical to the one that they tried to make.

That’s irrelevant, Jonathan Yellin, lead counsel for

Breitkreutz, said in an interview.

As a unit owner, Breitkreutz has a right under state law to

inspect records regardless of the reason, he said. All unit

owners who have requested to inspect the association’s

records “have their own reasons,” he said.

In addition to questioning Breitkreutz’s motives, the

association’s lawyers argued that a handful of factual

errors in her petition for arbitration proved her motives

were unpure. The petition was legally flawed, they said,

because it stated that the property manager received the

record inspection request on Oct. 13 and not Oct. 14. They

also claimed that calling her email a “follow-up” to her

record request was “yet another misrepresentation” because

the property manager received the email before the certified

letter.

The association’s arguments prevailed in a non-jury trial on

Dec. 20, 2018, before Palm Beach County Circuit Judge Donald

Hafele. The judge determined that Breitkreutz had the

responsibility to “carefully monitor her email” during the

five-day response window triggered by her record request.

‘Most boards are happy’ to provide records

Travis Moore, Florida-based lobbyist for the national

industry trade group Community Associations Institute, said

the Boca View hostilities are not typical of communities

across Florida.

“Most boards are happy to facilitate access to documents,”

Moore said by email. “Yes, sometimes the logistics

associated with record inspections become cumbersome. In

some cases, owners request record access for sport, spite or

simply to rile up the leadership and that leads to a

plethora of complaints to DBPR but those instances represent

a tiny fraction as record inspections take place every day

among Florida’s 50,000+ associations.”

Bergemann, of the unit owners’ advocacy group, says the way

it should work is, “The member making a request would get a

phone call: ‘How about coming in at 10 a.m. tomorrow?’”

Whatever the reason, that’s not the way it works at Boca

View Condominiums.

The Becker lawyers began their efforts to collect attorneys’

fees in June 2019, six months after the judge ruled against

Breitkreutz.

Citing testimony by Breitkreutz and Yellin that the Shefets

were paying her attorneys, the association filed a motion in

September 2019 to have the Shefets named as parties to the

suit so they could be billed for the fees. The Shefets

objected, saying they had no formal written agreement to

indemnify Breitkreutz.

Judge Hafele ruled that the association waited too long. The

Shefets could not be added to the suit six months after his

final ruling, he said.

The association appealed and lost. In all, it spent more

than two years trying to hold the Shefets responsible for

their fees.

On May 18, 2022, six years after Breitkreutz sent her

request to inspect the association’s financial records,

Hafele issued a judgment ordering Breitkreutz to pay the

association’s $395,554 legal bill for 1,234 hours that the

Becker team spent litigating the case. Those hours were

billed through February 2022 and included time spent in the

unsuccessful two-year effort pursuing fees from the Shefets.

Hafele’s ruling found that the $395,544 billing was

“necessary and reasonable” in light of the amount of

litigation required by Breitkreutz’s team’s “aggressive

defensive posture.”

In an email, Yellin said Breitkreutz should not have been

billed for the association’s pursuit of fees from the

Shefets. “How is it fair to award fees against a party that

had nothing to do with a post-judgment wild goose chase that

failed miserably?” he asked. “Shouldn’t the award of fees be

limited to the efforts taken by the prevailing party that

were actually successful?”

Two days later after the ruling ordering Breitkreutz to pay

all of the fees, the association filed a demand for a

detailed accounting of all of her assets and liabilities,

including tax returns, general ledgers, customer invoices,

vendor contracts, deeds, bank statements, stock

certificates, and broker statements.

Another record request

On Feb. 6, 2019, two months after Breitkreutz’s court loss,

Eleanor Lepselter filed her own request to inspect the

association’s financial records. Yellin would be her

authorized representative, Lepselter’s request stated. Eric

Estabanez, Boca View’s property manager, responded by

stating that only Lepselter or Yellin, and not both, would

be allowed to inspect the records.

Yellin and Lepselter both showed up at Estabanez’s office

for the scheduled inspection and were again told only one

would be allowed into the room with the records.

In an email to Estabanez filed in court, Yellin wrote that

Kuka, the association president, her brother Igly Kuka and

the board’s vice president and treasurer Giuseppe

Marcigilano “took turns coming out, trying to intimidate us

into giving up this fight, refusing to allow me to inspect

the records.”

Yellin recently recounted, “I wasn’t going to allow [Lepselter]

to go into that room by herself with them.”

In a pattern recalling Breitkreutz’s case, Lepselter filed a

complaint with DBPR and requested arbitration.

The association was wrong, the arbitrator ruled, in its

interpretation of a clause in state law that says records

must be made available to “the member or the authorized

representative of such member.” Clearly, the arbitrator

ruled, the language was written “in anticipation that a

member and her attorney would review the records together.”

The association was ordered to pay $500 in damages and make

the records available “immediately ... and at all times in

the future.”

Lepselter got neither. On Jan. 9, 2020, the association

filed suit against her to overturn the arbitrator’s ruling.

The suit said the arbitrator “misapprehended the law,” and

that Lepselter’s record request was “fatally flawed” and

made in “bad faith” on behalf of Cool Spaze.

Two and a half years and 236 filings later, the lawsuit

remains open.