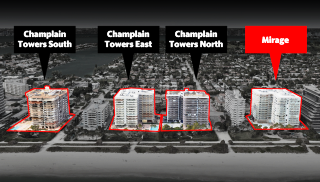

In the late 1970s, a group of Canadian developers swooped into Surfside, a golden-beached winter haven with a dysfunctional small-town government. There they laid the foundations for a cluster of high-rise condo buildings along the coastline just north of Miami Beach, three of which would carry the “Champlain” name. Their fourth tower, the Mirage on the Ocean, doesn’t have the same branding as Champlain Towers South, which partially collapsed in June, killing 98 people, or its sister towers, Champlain Towers North and East.

|

The Mirage on the Ocean condo tower in Surfside, pictured Oct. 2, 2021, was developed and designed by some of the same players who built Champlain Towers South. |

“The problems that we know about with the building that failed — putting that together with the cracks in this [Mirage] building — tell me that we do need to do a fairly thorough investigation of the structural design,” said Shankar Nair, an engineer based in Illinois with more than 50 years of experience designing large structures.

Still, Surfside has not asked its engineering consultant — whose charge is to examine the roots of the Champlain South collapse — to take a closer look at the Mirage, as it did for the similarly designed Champlain Towers North and East. Despite the overlaps between the buildings, Surfside will not even acknowledge that links exist between the Mirage and Champlain South. “Any connections between the Mirage and the Champlain Towers South are neither confirmed or dispositive at this point,” Malarie Dauginikas, the town’s spokesperson, wrote in an email. “The Town has not received any reports from the Mirage regarding the structural integrity of the building.”

|

In the 1970s, a group of Canadian developers swooped into small-town Surfside with plans to build four condo towers. It took more than 15 years. By the end, one of the towers, the Mirage on the Ocean, had a different name than the three Champlain-branded projects — obscuring its origins from residents and town officials after Champlain Towers South’s deadly collapse. |

Town council meetings grew infamous, serving as the staging area for a bribery caper involving the vice mayor, who was arrested in 1978. The town administration was helmed by a rotating cast of managers whose tenures often lasted only months. “Boy, were there fights,” Richard Aiken, who took over as town manager in June 1979, told the Herald. “Maybe not fistfights, but yelling and screaming at each other … We were caught in the middle so often and sometimes a glass of water was thrown at town councilmen up there on the dais, spraying back and forth. It was just mind boggling.”

Into this maelstrom of dysfunction stepped a group of self-made businessmen from Toronto, born in Europe. Several had survived the Holocaust. Nathan Reiber became the face of the consortium that would — through various partnerships and reconfigurations — build Champlain Towers South and Champlain Towers North, which both opened in 1981, as well as the Mirage on the Ocean and Champlain Towers East, which opened in the mid-1990s. A Toronto lawyer and developer, Reiber moved permanently to South Florida in the early 1980s after “abscond[ing] to Miami” when he was charged with tax evasion in Canada, according to a Hamilton Spectator article on his guilty plea in 1996. (A judge ordered him to pay a $60,000 fine.)

|

Construction scaffolding is seen near the entrance of the Mirage on Oct. 2, 2021. The tower, which has ties to the collapsed Champlain South, has been under renovation for about two years. |

They said they could help the town — offering to foot part of the bill for repairs needed to fix its beleaguered sewer system. But some elected officials were skeptical, worrying that any help they received from the developers would come with the expectation of something in return.

In late August 1979, the vice chairman of Surfside’s Planning and Zoning Board let loose as the board was grappling with the hefty task of reviewing Champlain South’s complex plans. “A lot of consternation has crept into this thing,” Joe Roberts said, according to meeting minutes. “What’s cooking here? … Nobody figures that the builder is going to give the town [funds] and not want something for it.” Aiken, the town manager, was a strong advocate for the approval of Champlain Towers North and South, according to newspaper articles and meeting minutes from the time. He pushed the town council to approve sewer repairs that would allow the towers to move forward and stayed on top of the Planning and Zoning Board — sometimes to the board’s annoyance. In late 1979, its chairman said the board felt “unduly pressured” by Aiken’s persistence. (Aiken was forced out of town government the next year after he was accused of peering through his neighbor’s window at their young daughter. He denied the accusation, saying he was looking for his dog, and the charges were dismissed. It was his second alleged infraction, having been arrested earlier that year by Fort Lauderdale police for soliciting prostitution as part of an undercover sting, an episode he described as “entrapment” at the time. Those charges were also dismissed.) Meanwhile, Surfside’s building department relied heavily on George Desharnais, its well-qualified but part-time inspector, to help its officials vet the plans. At points, Desharnais, too, showed his exasperation. A year after Champlain South was approved, Desharnais had difficulties arranging for bewildered planning board members to view the plans for the East tower in a timely manner, an episode he called “embarrassing,” according to meeting minutes.

The debate over sewer repairs and the building moratorium dragged into the summer of 1980, stalling Champlain South. When it was finally resolved, half of the repair funds, $200,000, came from the developers. Roberts, the vice chairman of the planning board, criticized exceptions granted by the town council, such as allowing a penthouse floor at Champlain South that pushed it beyond the town’s 12-story limit. “We were all sold a bill of goods,” he told the Herald in January 1981.

‘ONE TOUGH SON OF A BITCH’

Champlain Towers South and North sold out

after opening in 1981, helping launch Surfside’s

revitalization. The Mirage was a different story. A

partnership controlled by Abe Blankenstein, Joseph Fialkov,

Isadore Goldist and his brother Harry Goldlist bought the

land for the project in 1980, backed by a $12.5 million

mortgage. The developers laid pilings and foundations. Then

the bottom fell out of South Florida’s real estate market.

“Fortunately, all we had on the site was a hole in the

ground,” Blankenstein wrote in his biography.

“Unfortunately, while we waited, we had financial

obligations to the bank to make mortgage payments and that

money came out of our pockets.” For the rest of the decade

and into the early 1990s, the Mirage developers swapped

interests in the land and traded mortgages with each other

in a series of bewildering transactions. Peter Zalewski, a

South Florida condo market analyst, said the sales appeared

to be a common way developers protect themselves if they are

worried about losing their land. “If someone is going to

sue, they’re going to have to sue each particular

corporation,” Zalewski said. “It will be complicated as hell

for a creditor to go through and run down each of these

corporations. It drags everything out.” (The Mirage condo

association faced exactly that problem when it sued over

construction defects years later, one former board member

said. The court records were destroyed after the case was

settled.)

Finally, with the market back on the upswing, the developers

were able to restart construction in 1994, using the

existing pilings and building a 12-story condo tower on top

of the original foundation. The driving partners were

Isadore Goldlist and Blankenstein, according to Jerry

Kaufman, who joined their team as a partner in the early

1990s to handle sales and marketing. Goldlist and

Blankenstein originally branded the project “Richelieu

Towers” — after a character in The Three Musketeers — to

distinguish it from Champlain South and its sister towers,

since Nathan Reiber was not a partner. Other aspects

remained the same: Once again, William Friedman was the

architect, although the engineer and general contractor were

different. Kaufman said he would have preferred another

architect. “Friedman had a relationship with Izzie [Goldlist]

and Abe [Blankenstein]. He was not my choice,” he told the

Herald in an interview. “My choice would have been …

somebody more contemporary.” Friedman’s architectural

license was suspended for six months in the 1960s after sign

pylons at a building he designed collapsed during a

hurricane — something Kaufman said he was not aware of.

(Friedman died in 2018.) Kaufman did make other changes,

however. For instance, the project was renamed Mirage on the

Ocean, to broaden its appeal beyond French-speaking

Canadians. Reiber wasn’t formally involved in the Mirage,

but he still intervened occasionally out of loyalty to his

friends Goldist and Blankenstein. “He’d come into the sales

office from time to time and give me unsolicited advice,”

Kaufman remembered. “Nathan saw pricing as an orange to

squeeze and not a seed to plant. He thought I was being too

soft.” “He was one tough son of a bitch,” Kaufman said.

Where Reiber wore suits and ties, Goldlist and Blankenstein

favored shirtsleeves. “They were quiet, reserved gentlemen,”

said Kaufman, who added that he knew his former partners

would be heartbroken by the disaster at Champlain South.

“Most developers are extremely volatile,” he continued.

“They were humbled by the fact that they were refugees. …

Never did they say to me ‘cut this corner or cut that

corner’ or do anything out of the ordinary, which was

amazing to me. I grew up in the construction business and a

lot of people cut corners.” The Mirage opened in 1995, a

year after Champlain Towers East, which had suffered similar

delays and been taken over by a company registered to Gonda,

one of the original Champlain South partners. For

Blankenstein, the Mirage was a bet that paid off. Risk was

in his nature. In his biography, a friend remembered him as

a passionate gambler. “Las Vegas was his domain. He loved

the action,” the friend said. “He loved pitting himself

against the dealer. The actual amount of money involved was

secondary; the challenge of beating the house was the goal.

And no one ever knew if he won or lost.”

‘THEY DON’T KNOW WHAT THEY’RE DOING’

When Champlain Towers South collapsed, at

least one former Mirage resident connected the dots: Donald

Chapman, a retired architect who lived in the building and

briefly served on the board in the late 1990s. “There’s a

lot of similarities in the buildings. The floor plans are

very similar, a lot of cut and paste from one building to

the next,” Chapman told the Herald. The developers, he said,

appeared to be “tweaking those things as they marched up the

street building one after the other.” The L-shaped design

shared by all four buildings, he observed, was a way of

“squeezing more units onto a relatively narrow site” within

Surfside’s 12-story height limits, while also maximizing

ocean views.

Frank Barreras, who moved to the Mirage in the late 1990s

when the building was five years old, said there were

problems early on: water leaking through the garage onto

cars, balconies rusting, and a “huge crack” that opened up

in the pool deck. “I feel very lucky that I got out of

there,” said Barreras, who no longer lives in Surfside. The

Mirage’s problems have persisted and gotten worse, records

show. An engineer’s 2018 report found “numerous leaks” in

the garage and pool area and substantial problems on the

balconies, including spalling concrete, rusted steel

reinforcement and three broken “post-tension tendons”

sticking out from balcony edges. The Mirage, like Champlain

East, was built using a method called “post-tensioning,”

which strengthens reinforced concrete with steel bars, or

“tendons,” so it can withstand greater loads and accommodate

thinner slabs and longer distances between structural

supports. Champlain South and North are simpler reinforced

concrete structures. Engineers who reviewed the plans said

the pool deck at Champlain South had been cracking since day

one, because the slab was too thin and sagged in the large

spans between columns, placed up to 30 feet apart to

maximize parking space in the basement garage. The damage,

and especially the similarity of the cracking on the pool

deck, documented in 2018 is troubling, especially given the

Mirage’s post-tension construction, said Nair, the

Illinois-based engineer. “The whole point of post-tensioning

is to limit cracks or to prevent them,” he said. The three

broken post-tension tendons potentially indicate serious

structural problems, Nair added. “If there’s any uncertainty

at all about the post-tensioning, that’s a red flag and the

structural engineer should take it very seriously,” he said.

Larry Kibler, the former president of Miller & Solomon

General Contractors, which built the Mirage condo in the

mid-1990s, said that all concrete structures crack —

especially near the ocean — but it’s how condo associations

respond that determines whether it will become a significant

structural problem. “In my opinion, almost everything on

these towers … is all about how they maintain them going

forward,” Kibler said. “Do they do what they’re supposed to

do? Or do they kick the can down road?” The structural

engineer on revised plans for the Mirage in the early 1990s,

Zvonimir Belfranin, told the Herald he doesn’t remember

details of the building’s design, but said the current

problems seemed “fairly typical” for beachfront construction

— though post-tension cables breaking is “always a concern.”

“These are maintenance issues that need to be taken care of

as soon as possible,” he said. But large, deep cracks that

form as a result of flawed design can’t be fixed with

routine maintenance. Experts said the cause of the cracking

at the Mirage is hard to pinpoint without reviewing original

structural plans, the ones the town cannot currently find.

Drawings that are on file with the town of Surfside and

emails from the condo board detail plans to replace drains,

remove planters to lighten the load on the deck, install new

waterproofing and repair numerous cracks, including one that

was 40 feet long. Those fixes — along with a roof

replacement, fire safety repairs and a handful of other

items — were part of a $3 million special assessment on unit

owners. The building’s pool area, upper and lower decks, spa

and cabanas closed in early March 2020 for repairs,

according to an email to residents that estimated the work

would take four months. But the project still isn’t

finished.

As the repairs drag on, some Mirage residents say it has

only become harder to get real answers from the board.

Angela Elizalde Zavala, a longtime Mirage condo owner who

practiced law in Argentina before moving to the United

States in the 1980s, has long fought with the condo

association, which she described as incompetent. “My

impression is that the board, every year, makes this

building worse, period, because they don’t know what they’re

doing,” Zavala told the Herald. One of Zavala’s top

priorities has been documenting the true cost of the

building’s long-standing struggles with fire code issues.

The building has been out of code, documents suggest, since

at least 2016, when engineering consultants inspected the

damper system and found that an attempted replacement had

been botched. Residents interviewed by the Herald said that

the condo association started repairs, but the work has

stalled. Miami-Dade Fire Rescue inspectors visited the

Mirage in 2019, noting that the smoke dampers violated code

and that the association hadn’t properly tested its smoke

control system, according to a report. An MDFR spokesperson

told the Herald that the agency approved a permit for a new

damper installation at the Mirage and “the other violations

remain pending further enforcement.” Gregg Schlesinger, a

Fort Lauderdale general contractor and attorney, said it’s

rare for a building to remain out of fire code for several

years on end. “Fire is one of the most important things in a

building,” Schlesinger said. “You take care of it

immediately.” Gursky, the condo board’s attorney, denied

that the dampers were installed improperly and said the code

violations were related to testing rather than problems with

the fire protection system itself. When sent copies of the

reports documenting the issues, Gursky did not respond. He

contended that the board has been “completely forthcoming

and transparent” about the ongoing repairs, citing

construction updates emailed to residents and regular board

meetings. Condo board troubles, much like corrosion and

saltwater intrusion, are a staple of South Florida’s

beachfront residential buildings. Chapman, the retired

architect, said he moved out of the Mirage in the late 1990s

because of a nasty board fight involving a building manager

who was fired for alleged financial misconduct, then rehired

at the next meeting. “It’s the worst politics in the world,”

Chapman said. “Living here [in the Miami area] is like

living in paradise, except for the condo boards.”

‘THEY NEED TO CHECK EVERY BUILDING’

There are substantive differences between

the Mirage and Champlain Towers South, experts told the

Herald. Those include the structural engineer and general

contractor who brought the project to fruition in the 1990s,

as well as the building’s post-tensioned reinforced concrete

construction. (It’s not clear from available records which

engineering firm worked on the Mirage site in the early

1980s, but the names of an engineer and general contractor

for CTS appear on early permits there.) Abieyuwa Aghayere, a

Drexel University engineering researcher, said limited

architectural drawings appear to show that the Mirage — like

Champlain Towers East — has more robust columns and

better-designed reinforced concrete core walls, known as

shear walls. But engineers said that without reviewing the

Mirage’s complete structural plans and conducting a thorough

investigation, it’s impossible to know whether it might

suffer from the confluence of design, construction and

maintenance flaws that brought down half of Champlain South.

To better judge a building’s structural integrity and

possibly prevent another horrific collapse, engineers should

review original plans, test concrete strength and scan for

proper rebar placement, Aghayere said. Those steps often

aren’t taken — and it’s not clear whether they have happened

at the Mirage.

“Patching the external symptoms of what’s going on does not

prevent the continuance of whatever is going on internally,”

Aghayere said. The town of Surfside hasn’t pressed the issue

beyond recommending below-ground and other structural

testing, guidance that was distributed to all properties

east of Collins Avenue in July. Dauginikas, the town’s

spokesperson, noted that because the Mirage is less than 40

years old, the town has no obligation under current law to

recertify that it’s safe. Allyn Kilsheimer, the engineer the

town hired to investigate the Champlain South collapse, was

directed in July to conduct cursory reviews of several

buildings in Surfside. That included Champlain North — whose

design most closely resembles that of Champlain South — as

well as Champlain East.

But the Mirage was not on the list. Kilsheimer said town

officials informed him recently about its ties to Champlain

South, but told the Herald he believes those ties would be

more significant if the buildings shared a structural

engineer and general contractor. Nonetheless, Kilsheimer

said, if the town directed him to look into the state of the

Mirage, he would. Some residents hope that happens. “They

need to check every building, every property, in the town of

Surfside,” said Ernestina Jeronimides, 81, a longtime Mirage

resident. “This is their job.”